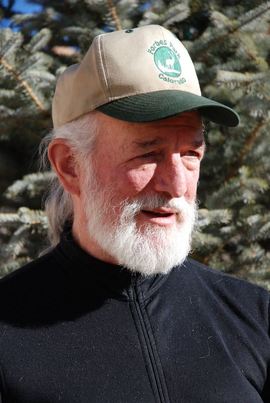

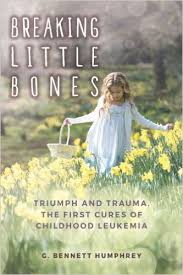

G. Bennett Humphrey’s historical non-fiction/memoir: BREAKING LITTLE BONES, Triumph and Trauma, The First Cures of Childhood leukemia, (2016) describes his one year spent as a clinical associate on the children’s leukemia ward, 2 East, at the National Cancer Institute, NIH, from July 1, 1964 through June 30, 1965. From 1966 to 2005, he pursued a career in pediatric oncology. He has been a visiting professor in the US, Europe and Japan and was listed in the 1993-1994 edition of Who’s Who in the World. In retirement, Ben’s activities included; long distant cycling, hiking, canine care, outdoor adventures in Colorado with grandchildren, and writing, and publishing prose and poetry. One poem from his chapbook, The Magpie Cries, (2016) resulted in his being named Senior Poet Laureate of Colorado for 2013, and he received a welcome review of BREAKING LITTLE BONES by Kirkus Reviews in 2017 and a positive judge’s critique for the 25th Annual Writer’s Digest Contest 2017. I was a very ambitious and very immature boy in 1955. I wanted a career in academic medicine and I was lucky enough to be accepted into the University of Chicago’s MD/PhD program. Nine years later I had: my MD, a PhD in biochemistry, completed an internship and two years of residency in Internal Medicine, and studied for one year in a research lab in Germany. I’d been a busy boy, and I was still ambitious and immature. I had to complete the last year of residency in internal medicine and a two-year fellowship in the subspecialty of my choice, Hematology. I’d be 35 years old before I could look for a job. Big Problem: The Vietnam war was heating up, and the military needed doctors. Two years of military service would be a zip on my Curriculum Vita, one’s job resume in academia. There was an alternative possibility: the Yellow Berets. The National Institutes of Health, NIH, had a program for clinical associates: two years as a commissioned officer in the U. S. Public Health Service. An appointment to NIH was a big deal - an anti-zip. I applied and got in. Bigger Problem: I was one of three physicians to work on the pediatric leukemia ward, called 2 East, at the Clinical Center on the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland. All of my training was in adult medicine. What did I know about children? -Zip. One of my colleagues was also an internist, Jerry Sandler, and the other was a pediatrician, Rick Lottsfeldt, who had completed his fellowship in pediatric oncology. During wars, friendships are forged under fire watching friends die. Our friendship would be forged on this unit, under fire from senior staff, and the friends we’d watch die were the children on 2 East. Even Bigger Problem: Adult patients have relatives; children have mothers. Mothers! What did I know about mothers? Nothing. For me as an internist, a mother was a caring adult having years of experience with a pediatric person. A knowledgeable woman who could understand an illiterate infant’s needs, whose day was filled with interruptions and dirty diapers and who for some inexplicable reason wasn’t an alcoholic. But my problems turned into life experiences that began on day one. A nurse introduced me to my patients. In the first room, a three-year-old boy sat among a zoo of stuffed animals. He appeared in no distress -- apparently indifferent to the dried blood covering his face and hands. He clutched a teddy bear also coated with blood. When Billy offered me his bloodstained bear, I took it, pretended to examine the abdomen, and returned the bear with a smile. He smiled back. In the past, as an internist, I was often given a bottle of booze by a grateful patient. Now a child had trusted me with his most prized possession. The nurse told me that not everybody was allowed to hold that bear. I was deeply moved, and my year on 2 East would be full of such encounters. Kids are neat; they cope better than adults. It’s a privilege to be taken into their world, to bond with them. I had much to learn about caring for patients and much of that would come from the nurses. Doctors treat; nurses care. At the end of rounds on that first morning, I took a moment to reflect on the nurse. Her name tag read “Morgan.” A short, peppy attractive young woman, she had touched each child on the shoulder while introducing me. It was a little gesture but an important bridge of love between a patient and nurse. I would witness these acts of caring for the next year. The mothers would teach me, among other things, about the daily task of living one’s ethics and discovering the hues of love. I would stand in awe of these compassionate women who used a variety of coping styles. One of the few things God got right was creating Mothers and Nurses. “What’s my story?” In addition to the above, I would be part of two events. Firstly, a paradigm shift in the medical attitude towards childhood leukemia. Generally considered a uniformly fatal disease, the chemotherapy under investigation at NIH would result in a 15 percent cure rate. A few cures are hard to see when most of your patients die. Secondly, I would undergo a transformation from an internist interested in basic research to a physician who would leave internal medicine, retrain and become a pediatric oncologist devoted to clinical research. For 50 years, I’ve known I’ve wanted to capture this one pivotal year, 1964, of my life in a memoir. But how would that be possible? I had absolutely no training in creative writing, and I would have to deal with a lifelong disability -- dyslexia. I had written scientific articles, clinical reports, book chapters and even books in pediatric oncology. Good practice in dull writing. Ironically, my introduction to creative writing started with five years, 2005 to 2010, of studying, reading, workshops and publishing poems. Finishing Line Press, Georgetown, Kentucky, even published a collection of poems, The Magpie Cried, 2013. One poem from that collection resulted in my being named Senior Poet Laureate of Colorado for 2013. What a wonderful way to spend one’s time and energy. In 2010, I started to work in prose. My goal: capture that one pivotal year. I was lucky in have valuable feedback and critiques from over 20 authors, six of whom deserve special mention because they read multiple drafts of my manuscript: the members of the Fort Garland Literary Society, Mary Lampe, Francie Hall, and Rhonda Borders; Annie Dawid, award-winning author and retired Professor of English, who was my tutor in writing; Summer Wood, award-winning author and recipient of the 2012 Willa Award; and Pat Nolan, poet, artist and a mother who has had to endure the loss of a child. The manuscripts went through 15 drafts. I’m not very bright, but I am tenacious. After a year of corresponding and meeting literary agents who felt no one wants to read about the death of children, I had a very enjoyable experience self-publishing with the help of the CreateSpace staff from Amazon. Breaking Little Bones was published in 2016. There have been 22 Amazon reader reviews, and positive critiques from Kirkus Reviews and the Writers Digest 25th annual contest. I’m still ambitious. I’d like to find a small press or a literature agent for Breaking Little Bones, but my immaturity gave way along time ago to gratitude for spending my academic career in pediatric oncology. Breaking Little Bones In this profound, complex story, G. Bennett Humphrey, MD, PhD, chronicles his year on 2 East, a pediatric leukemia floor. Doctors are fighting a presumedmortality rate of 100 percent, but the cost of finding a cure weighs heavily on their hearts. The cure rate for the children of 2 East in 1964 will turn out to be 15 percent. With almost no training in pediatrics and no experience with chemotherapy, the author confronts an entirely different world. From the beginning he is amazed by the strength of the mothers, the compassion of the nurses, and the admirable ways the children themselves cope with this devastating illness. Breaking Little Bones combines the personal and the scientific in poignant moments. It is both an overview of the revolutionary medical progress made in treating acute lymphocytic leukemia in 1964 and an honest narrative of what it was like to be there. Humphrey knew these kids. He knew Todd, who loved words, and Polly, who held her bald head proudly. He formed a brotherly bond with his team members, and he had to figure out his own unique way to cope with the grief. This transformative look into one of the most heartbreaking areas of medicine digs deep, revealing what we can learn about truly living from those facing an early death. Check out G. Bennett Humphrey's website here! Where to Buy Breaking Little Bones

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm generally pulled in a million different directions and I wouldn't trade it for the world. Here's a glimpse of my life - hope you enjoy it! And if there's a big lapse between posts, well, that's the way life goes in Amy's world. Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

|

Copyright 2024 by Amy Rivers. All rights reserved. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed